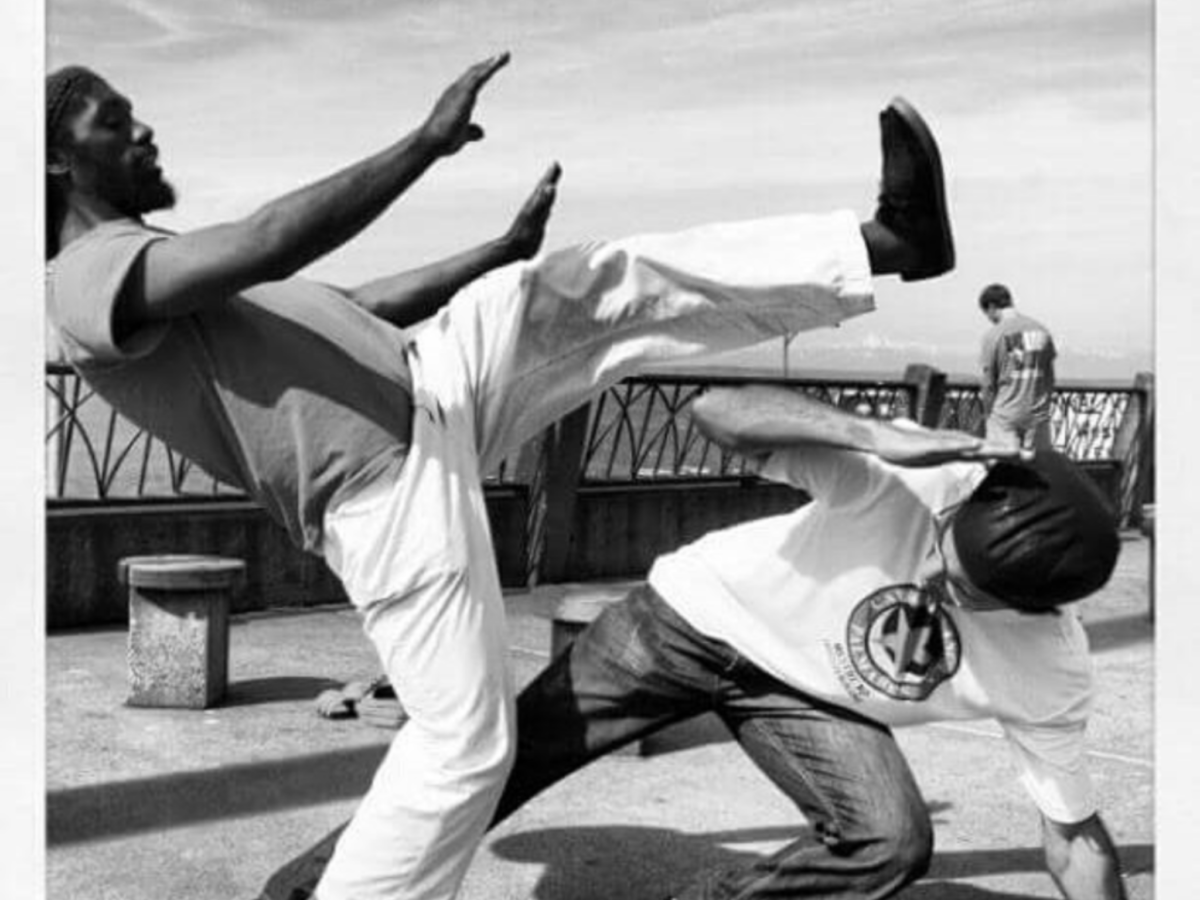

A tribute to a great capoeirista and a look at how the Brazilian martial art honors a passing member.

On August 13th, 2015, William Darnell Robinson went for a swim with his brother in a river near the Big Horn trail in Spokane, WA. From the outset, this would seem absolutely safe for Robinson; he was an incredibly fit 31-year-old who was known as one of the best capoeiristas in the local area. A swim in the river was trivial compared to physical feats of which he was capable, but that day the water was especially strong. Both brothers got caught in the current. One made it out. The other didn’t.

What happened to Robinson, who in capoeira circles was affectionately known as “Mugunje”, sent shock throughout the community. Ten days after his passing, over a hundred people showed up to the small studio of his home school, the Seattle Capoeira Center, to take part in a farewell “roda”, otherwise known as the circular formation of players and musicians that surround two capoeiristas as they play their game. Practitioners from different groups and different eras came to pay their respects. Family and friends from outside of the capoeira community made an appearance as well. The ceremony began by opening the floor for anyone to speak words about the fallen member. Stories, both heartfelt and humorous, were passed around as those in attendance smiled in reminiscence, a sentiment soon overtaken by a melancholic reminder that the stories’ protagonist was no longer with them.

He was described as a “mystic”, someone who had a different understanding of his surroundings, which was a fitting term evidenced in the way he lived his life. People recounted the times he ambled into class dressed in overalls while carrying a bag of mixed nuts, or about the time when in getting lost in the forest, he ate the pine needles off the trees to ward off the hunger pains. In the few times I met him personally, it was apparent that he lived life in a kinder way, and had a relationship with the world that suggested he had come to peace with it. Once the final anecdote was given, those present shared a moment of silence, and the ceremonial roda began. To open, one of the rituals of capoeira to honor its fallen, the “toque de Iuná”, was played.

“The primary thing that we do [when someone passes] is we play a capoeira rhythm called ‘Iuná’ that doesn’t have any capoeira play involved, but only the rhythm,” says Syed Taqi, the Contramestre of the center who goes by the title “Contramestre Mangangá”. He hums out the rhythm with his lips. “That kind of symbolizes the berimbau [capoeira instrument] crying for the capoeirista that passed, like the person holds it in, then it just lets it out. Holds it in, and then lets it out.”

The “Iuná” traditionally follows a moment of silence, and symbolizes mourning, not only for its honoree, but for all that has passed away. The ritual is akin to boxing’s “Final Ten Count”—the 10-bell toll done at the first major bout following the passing of a notable figure in the community. For Mugunje, his contribution to the Seattle Capoeira Center was not only notable, but also key to making what the center is today.

The studio previous was located on the bottom floor of an apartment complex tiled half of concrete, half of wood flooring, not exactly the ideal surface for a capoeira practice. Before that the center held court in other spaces, but found difficulty in establishing itself due to financial limitations. This all changed when the center was able to firmly establish their kids’ program by renting a fully wood-tiled space in a dance studio next door—a cost paid entirely out of Mugunje’s own pocket—and the income generated from the program is a large part as to why the center has the more permanent space it has today. When tracing his influence back even further, Mugunje was the whole reason the Contramestre chose to become involved in the first place.

“Man he’s the one that got me to want to teach capoeira,” Mangangá tells me. “He was my first student. He convinced me to do it. He wanted to learn with me so I just started teaching him, and then after that I realized that I loved capoeira more than just a hobby, like I want to do it for the rest of my life. I want to share capoeira with anybody that’s ever needed it.”

Over the years, the Seattle Capoeira Angola Palmares group has gone through a number of transformations. They have roots in the oldest capoeira school in Washington State, and have held their own group for nearly eight years. Officially, the group is now recognized as the “Panteras Dos Palmares—Capoeira Angola Palmares”, the addition made when Aaron Dixon, a member of the original Black Panther Party and former captain of the Seattle chapter, endorsed the center to make it the only martial arts academy to be affiliated with the Black Panther Party. This left a responsibility for the center to uplift people of color through their activities, a principle embedded into the Panther’s own operations. Mangangá has since used the art to connect Afro-Brazilian history with black American history, and also as a forum for social liberation, much like both the Panthers and capoeira did in their time. According to Dixon, had the Panthers knew about capoeira in their heyday, the practice would have surely been adopted for its roots in African heritage.

While history has left a controversial image of the Black Panther Party—most notably the images of uniformed men and women patrolling their neighborhoods with visible firearms—it is important to consider how media manipulations of the times can discount the less publicized deeds of the party. Former FBI president J. Edgar Hoover himself stated that the Panther’s greatest threat to the country was seen not in their armed presence, but in their Free Children’s Breakfast Program. This suggested that the true “threat” was not in an armed revolution, but in community reclamation. In that vein, Mangangá certainly carries the same spirit, because for him, the practice isn’t only about capoeira.

“I got kids growing up with me from 4 or 5 years old, who are like 11 now and they want to do capoeira for the rest of their life. They live capoeira. It’s not only doing capoeira, it’s living capoeira,” Mangangá says. “So back home in Brazil, capoeira is an alternative school, it wasn’t just a marital arts academy, like it teaches you everything from reading, to colonial history, to music, to dance, to Afro-Brazilian culture, to math, science, whatever your Mestre was able to provide, he taught. It’s not only fighting. That’s the thing. People think it’s only fighting, but it’s more than that.”

For Mangangá, it was a saving grace. Growing up with the notorious Latin Kings in a gang-infested northside Chicago neighborhood, Mangangá was well on his way down that path until capoeira changed his trajectory. Through reading and translating songs, the practice gave him the tools for an education, which led him to a community college where he first met Mugunje, and as mentioned, the friendship led him to where he is now. The loss to him is much more than merely losing a student.

“He’s like the strongest—spiritually, emotionally and physically—person I ever met, but also the most gentle. Mugunje trained for 11 years, and he’s never hurt one person. To be a martial artist and have that much control…that’s how strong he was. He was so gentle and so skilled, so passionate about our lineage…our lineage meaning all the ancestors, and just to include Mugunje in our ancestors now, it’s a trip, you know what I mean?” Mangangá tells me. “[He] was my closest friend that passed away since my dad, and my dad passed away when I was 12, so nothing like this has even happened. It’s just crazy, like I had one perfect day with him, just talking to him and building on the future, and the next day, he was gone.”

The two had chatted for about an hour the day before, strategizing their plans of expansion and forming a group in Spokane, a city four hours from Seattle and also Mugunje’s hometown. They had also continued their discussion on the development of “CapoeiraLife”, a non-profit education program targeting at-risk youth to become involved in the art form. The program is set to go on and will now offer a William ‘Mugunje’ Robinson scholarship for youth recipients to participate without cost.

Another ritual common in capoeira circles is administered at the funeral. A small roda is performed and the involved group members stomp on the gravesite until the dirt mound is pounded flat, symbolic of the group sending their member home. This ritual will not be held for Mugunje, as cremation has been the chosen funeral right, though the group has still come together in other ways. At the end of the roda, Mangangá handed the mother of the deceased an envelope filled with $500 dollars of his own money to go towards burial costs, an amount that was matched and exceeded that day to a final total of about $1500. The contribution is part of a larger fund, which in addition to funeral costs will go towards bringing Mugunje’s daughter back from Germany, and general support towards the family. Before his passing, Mugunje worked countless hours at Field Roast food factories, and always contributed part of the paycheck back home.

A parent is never really ready to say goodbye to their child, especially when they are forced to do so before their own time. But when it does happen, a community makes the transition a little easier. It is the community that brings the pieces of a person together, so that those coming to say goodbye can see a more complete version of who they were.

“This memorial was beautiful. This was excellent. This was something that William would have wanted,” says Michael Akridge Davis, the father of Mugunje. “It gave other family members a chance to see what he was into. A lot of them would see him doing flips, backflips and doing the art, but they didn’t know what it was like.”

For the mother, Jacquelyn Robinson, the ceremony was not only a display of her son’s life, but also another chance to give a final farewell.

“His spirit was here. His spirit was here, and looking at all his other family, I know he was loved. I felt the love of the capoeira family,” says Robinson. “He’s going to be missed. If you think about his name, William Darnell Robinson a.k.a. Mugunje, he’s gonna be in your heart.”

To help support the family, donate here.

To learn more about the Seattle Capoeira Center, please visit their website.

https://www.vice.com/en/article/bme98q/how-capoeira-honors-one-of-its-own